- Activities

MAPS is a collective effort proposing new ways and approaches of storytelling to address the world's changing environment and societies.

MORE- Works

- Cultural

- Education

- Collective projects

- Members

MAPS brings together various dedicated professionals who want to start a new adventure and learn from each other in the process.

MORE- Photographers

- Creatives

- Contributors

- Foundation

Series

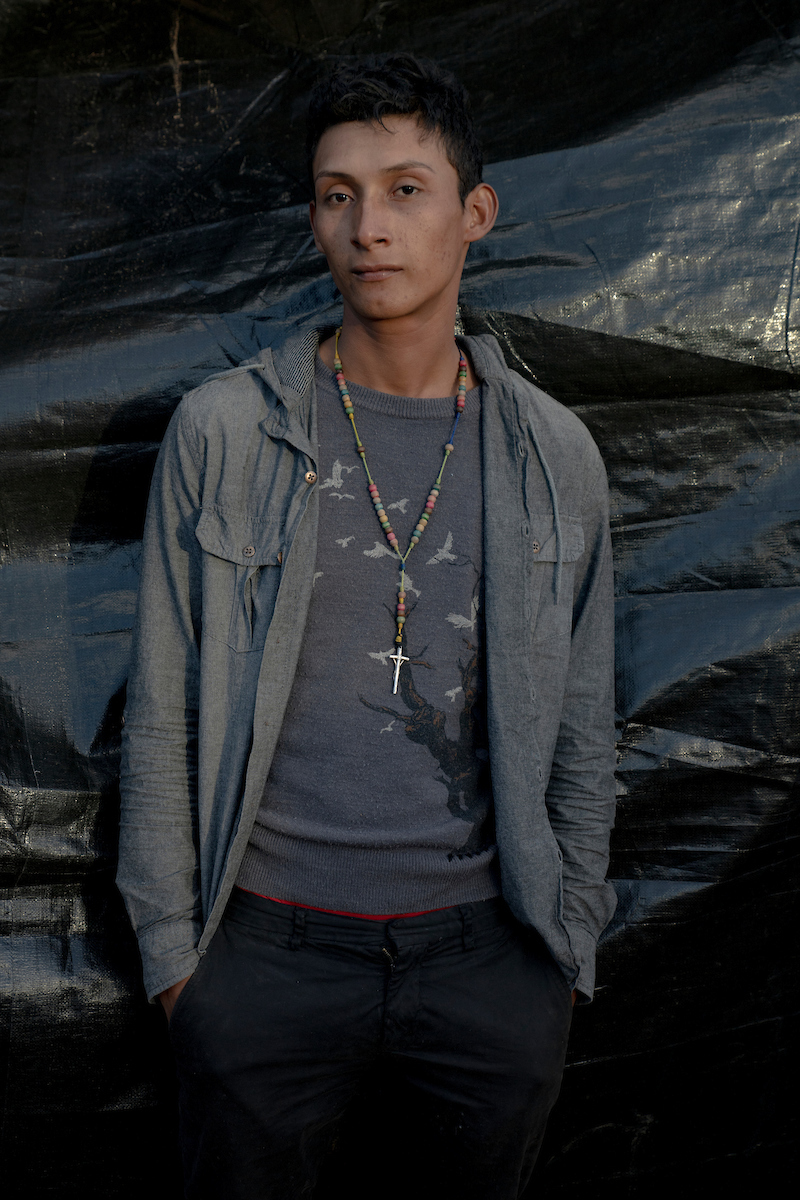

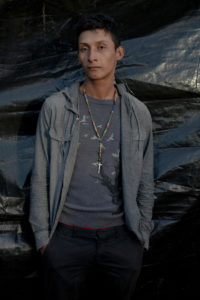

Caravana Migrante, Tijuana

Kitra Cahana

Until it reached the US border in mid-November, the migrant caravan that set out from San Pedro Sula, Honduras, on October 12 had largely been a success. Leaving that crime-benighted city with only 160 members, the caravan ballooned to ten times that size by the third day, as people streamed in to join from all over Honduras and neighboring El Salvador. By the time the group reached southern Mexico, having overwhelmed authorities at both the Guatemalan and Mexican borders, the United Nations estimated that there were over 7,000 members—easily the largest caravan yet to come out of Central America. The unprecedented spectacle quickly captured the world’s attention and became a symbol for what is becoming known as the ‘Central American Exodus’—the mass movement of people fleeing staggering, relentless violence and abject poverty in the ‘Northern Triangle’ countries of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

In the US, however, the caravan was becoming a symbol for something else. Seizing on the optics of 7,000 bedraggled people marching northward as incontrovertible proof that America was under siege by vast mobs of mystery invaders, President Trump turned the caravan into the cornerstone of his pre-midterm election rhetoric.

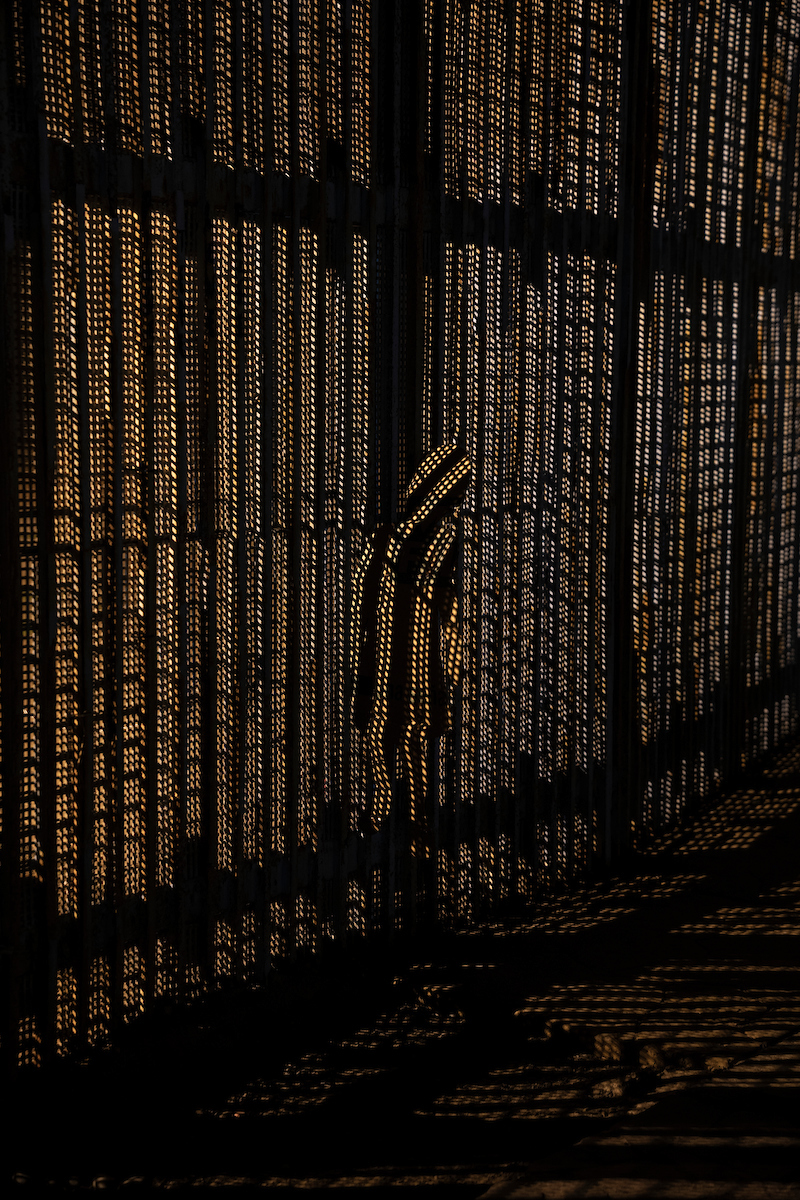

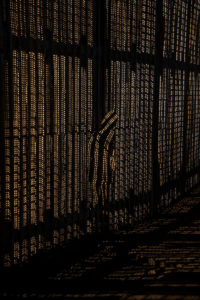

Mid-November, the caravan arrived in Tijuana, and almost immediately the mood darkened. The migrants saw the US border for the first time: the floodlights, cameras, motion sensors, the two imposing metal walls festooned by razor-sharp concertina wire, the rigorous patrols of the Customs and Border Protection officers.

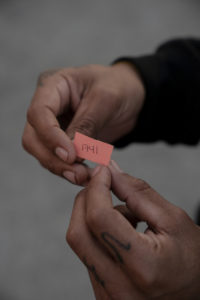

What remains of the caravan is now living a confused and precarious existence in the shadow of the American border. Trapped between life-threatening violence and an unsympathetic, byzantine US immigration system, the migrants are in limbo—uncertain what lies ahead for themselves and their loved ones, unsure who to trust, and bewildered by the whirlwind of false information and rumors in constant circulation. After a grueling 4,000 kilometer journey, the dream of America is agonizingly close. At the Tijuana beach, where the border fence extends some 100 meters into the Pacific, migrants often walk to the water’s edge and peer through the steel slats of the fence to the US soil on the other side. They can reach through and touch the country that they hope will give them sanctuary, a final respite from the chaos of their homelands. But for now, theirs is only an

American pipe dream, tangible enough to pull at the soul, but illusory enough to crush it.

Text by Fletcher Reveley (extract)