- Activities

MAPS is a collective effort proposing new ways and approaches of storytelling to address the world's changing environment and societies.

MORE- Works

- Cultural

- Education

- Collective projects

- Members

MAPS brings together various dedicated professionals who want to start a new adventure and learn from each other in the process.

MORE- Photographers

- Creatives

- Contributors

- Foundation

Storytelling

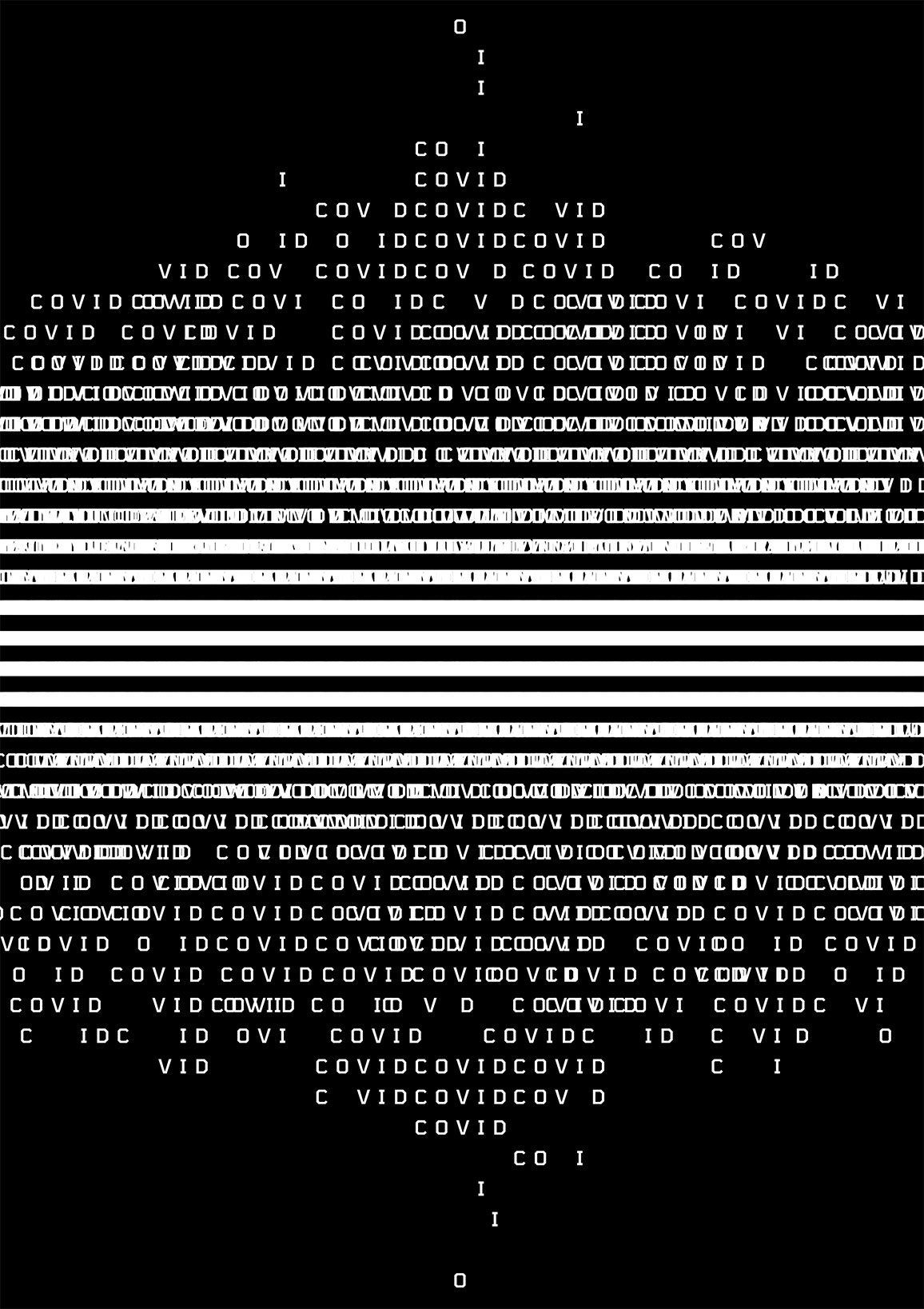

In different parts of the world, MAPS photographers and creatives all spent weeks on lockdown, one of the measures taken by many countries to face the COVID-19 pandemic.

Coping

Chapter 1 — Roots

In the face of a global, unprecedented crisis, coping may mean to find shelter within the inner core of what constitutes a safe environment. Holding onto the thread of transmission, finding comfort in familiar places, with loved ones.

“Pandemic” graphic creation by Chiqui Garcia

BY CAROLINE LAMARCHE

Writer

What we see here makes us think of our daily lives in a strange way.

And yet these photographers have worked up until now in more turbulent parts of the world. Far from our ordinary lives. Close (or so we thought) to the “real” issues, the “real” problems.

Here, what we discover to our surprise is mostly stories that take the form of private or family diaries, of restricted walks.

But if we really think about it, was what they were doing before so remarkable? Wasn’t it, on the contrary, as normal and obvious as what human beings do day after day, and have always done: going to the frontline of their own lives, occupying the place for which they are destined, by circumstance or by vocation?

Coping.

For some, it happens in a harsh, mineral light. For others, in a shimmering darkness where the buds seem to cry out. For others still, the roots are exposed, the flow of life is broken, the city becomes a frightening ghost town, a bird falls far from the trees.

And always the fragility of the two extremes. The child. The grandparent. The two unite, defying the orders that try to separate them, refusing the abrupt segregation of the generations. They rest side by side, their sleep either troubled or deep. They are entrusted to us. They illuminate us.

But what about us?

What of the generation in the middle, torn between compassion and anxiety, gentleness and harassment? Who are we, what are we becoming?

Adults.

Etymologically: creatures who have reached the end of their growth. Or at least who are coming to the end of a form of growth. Who identify this end in the state of the world and in their own lives.

Because of circumstances, this stage is being experienced in a kind of withdrawal. A third place.

A place from which something else may emerge. Something that is barely visible, but can rather be sensed in the vibration of the image. Something swaddled in beauty, emptiness and patience, which points, by antiphrasis, to another frontline, absent from the image because unapproachable.

The frontline of the unconfined, the emergency doctors, the nurses whose days used to be structured, their work organised, their tasks identified, and who today find themselves fighters with no chance of retreat, no protection and no witness other than abstract statistics and the news bulletins that beat away at citizens day after day, hour after hour, minute after minute.

At the same time, photographers who chose lives of instability and risk in faraway places are now forbidden, by public health decree, from going to those places in their own environment where the most dangerous forms of suffering are present: in the enclosure of domestic violence, in the supercharged surroundings of the hospital, the retirement home, the business threatened with bankruptcy, in the stifling limits of cramped apartments.

Here they are, these witnesses through the image, powerless to document anything other than what disrupts, or, by default, structures their own confinement.

Confronted with the disarray of governments, the confusion of scientists, the mobilisation of every available carer, they have suddenly become people who take care, day by day, of their nearest and dearest.

Vigilant.

Persistent

Connected.

(translated by Howard Curtis)

With Mom and Dad

BY JOHN TROTTER

After my 89-year-old father was hospitalized in late February, I bought a one-way ticket to Missouri to come help him and my mother, packing only enough for a week or two. But when I turned around from my dad’s bedside, the tidal wave of COVID-19 was already looming over all that I had assumed about my own future and the future of the world.

My father’s immune system was weakened by his recent chemotherapy and it quickly became clear to us all that he and my mother needed to isolate in their home, once we could get him there, and that I couldn’t possibly leave them to do that alone. So, I am here, for the foreseeable, yet unimaginable future, trying to be the best son that I can be.

“I am here, for the foreseeable, yet unimaginable future, trying to be the best son that I can be”

In the room where I sleep, I see two pictures joined in a single frame of my parents, just before their 1954 marriage. Not long after those pictures were taken, my father entered the Epidemic Intelligence Service with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and immediately began working on the “Asian” Flu Pandemic of 1957, the second major influenza pandemic of the 20th Century. He was 26-years-old. Now, at age 89, socially isolated in the home he’s shared with my mother for over a half-century, he knows absolutely why it must be like this, though he never foresaw that such a time would come to pass so late in life.

Virus Diary

BY CÉDRIC GERBEHAYE

When I was young, my grandfather often told me that if ever there was a war we all should live in the countryside. Today my grandfather is no longer with us and we are not at war but we are living a historical moment. I decided to step back and take my daughter to a remote place far from the city.

“I decided to step back and take my daughter to a remote place far from the city”

“My father told me about America”

BY HANNAH REYES MORALES

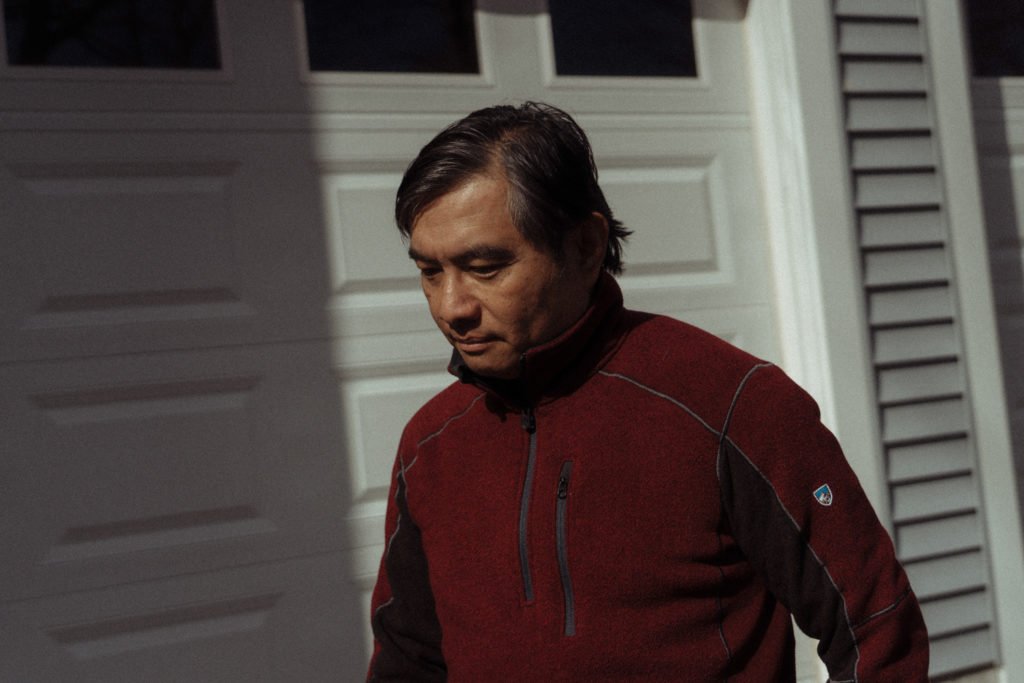

When the Philippine government announced that Manila would go on lockdown to prevent the spread of COVID-19, my husband and I made the difficult choice to fly to America.

As the pandemic disrupted life across the globe, we looked at our options for sheltering in place. Like many others the choices in front of us were troublesome.

Our entire life is in the Philippines, where our overburdened healthcare system has the ratio of one doctor for every 33,000 patients. As of the time of this writing, less than a dozen tests are being performed per million people. His family is in the US, which has now become the global epicentre of the virus.

He believed we would be safest with his family in Massachusetts. In this little part of New England, we are taking shelter in the space they built in America for generations.

They moved here across different times of turbulence for Philippine society. Jon’s grandfather, Papa Beck, moved to Quincy during martial law. He was among the first Asians to live in Quincy. His father was a guerrilla who worked with the US Navy. ‘My father told me about America,’ Papa Beck said. His son Dennis, my husband’s father, moved during the Philippine coup attempts in the late 80’s.

As the Philippine government announced the military’s arrival into our city, Philippine society was reminded of martial law. My husband Jon returned to America for the first time in years. When we landed in the US Jon’s father seemed relieved. He left the Philippines so we could make this choice. Here is the life and safety that they have built for generations. Here is where we are sheltering in peace.

We find safety inside the physical structure of homes. Staying home means safety from the virus, but also from the rising xenophobia against Asians and Asian Americans. On television Trump continues to call COVID-19 the ‘Chinese virus.’ While shopping for groceries I hear my husband speak a little louder, making his American accent more pronounced, changing his body language so we might appear less of a threat in a country where he grew up being called chink and spic.

‘You get used to hard things,’ Papa Beck once told me. Though I am not moving here I am seeing America through a gaze that isn’t so far from theirs when they first arrived. As we enter this unsettling period of history I am reminded of the fragility of place, and the importance of what others built long ago so we can breathe a little easier.

Under the bleak New England sky, and in grief and desperation, I hold on to traces of things that feel like home.

Still, Life

BY JUSTYNA MIELNIKIEWICZ

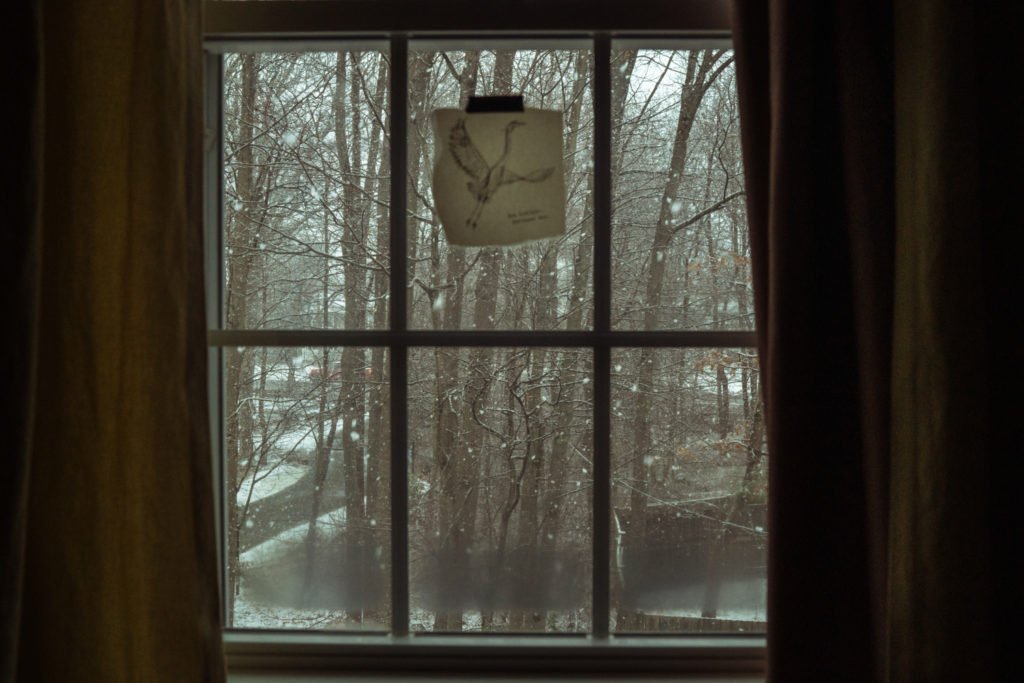

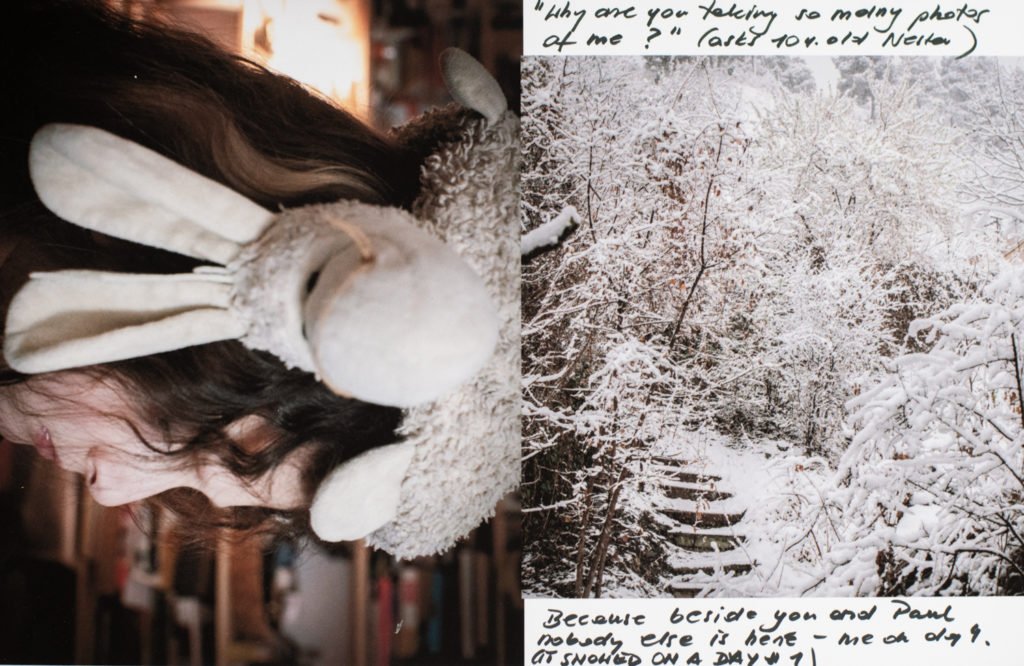

Georgia had already closed schools on March 1st, shortly after I got back in extremis from Poland, before the country closed all borders. For my 10 year-old daughter Nestan, it was the start of her ongoing long holidays with 3 hours of school a day plus homework. Paul, my husband, became the designated “hunter” – leaving our cave to fetch food and be prepared as facilities were closing down, despite Georgia having only 49 cases at that point and no casualties.

My confinement became all about my daughter Nestan. I could not leave the house. She finally had both her parents 24 hours a day for herself and seemed very happy. On day one of our shared isolation, snow fell – so unusual in Tbilisi at this time of year – and she ran out to make a snowman. It reminded me that at around her age, I experienced martial law in Poland, in December 1981. A strange man with glasses in an army uniform announced “something important” during a time-slot allocated for a children’s morning program. There was snow outside, my parents were home, as it was Sunday, and yay! No school!

“We parents try to keep our fears in check and non-verbal so our daughter can enjoy her time worry- free and savor a sense of security we grown-ups are losing so rapidly”

As of my return from Poland, I was obligated to undergo 14 days of quarantine. I had to keep a safe distance from my family. A 50mm lens seemed to be the best connection I could retain. After my quarantine finished we moved to the village house, where we usually spend summers. Soon after that, Tbilisi was shut down.

We parents try to keep our fears in check and non-verbal so our daughter can enjoy her time worry- free and savor a sense of security we grown-ups are losing so rapidly. It is not easy but being where we are, it seems easier.

By its nature, the village is synonymous with isolation and social distance. It feels more natural here than in the city. As none of us really know how and what we really feel, we follow a current. Day by day with everything that comes with it.

More chapters from the Coping collective project

In confinement, yesterday and tomorrow have been replaced by an endless today. Time is standing still.

Every crisis involves an aftermath. How to apprehend it, how to imagine rebuilding our future lives in the midst of the turmoil?

More Series by Maps Members

Youth for Climate: New York, Brussels and Lausanne

Maps Members

All over the world, young people take to the streets to demand action on climate change. John Vink has been…

MoreBest Images of 2017

Maps Members

A selection from the best images of 2017 by MAPS photographers

MoreThis was 2019

Maps Members

2019 has been a time of exploration and discoveries. Of reflection and coming together. Of defining and redefining what MAPS…

More