- Activities

MAPS is a collective effort proposing new ways and approaches of storytelling to address the world's changing environment and societies.

MORE- Works

- Cultural

- Education

- Collective projects

- Members

MAPS brings together various dedicated professionals who want to start a new adventure and learn from each other in the process.

MORE- Photographers

- Creatives

- Contributors

- Foundation

Storytelling

In different parts of the world, MAPS photographers and creatives all spent weeks on lockdown, one of the measures taken by many countries to face the COVID-19 pandemic.

Coping

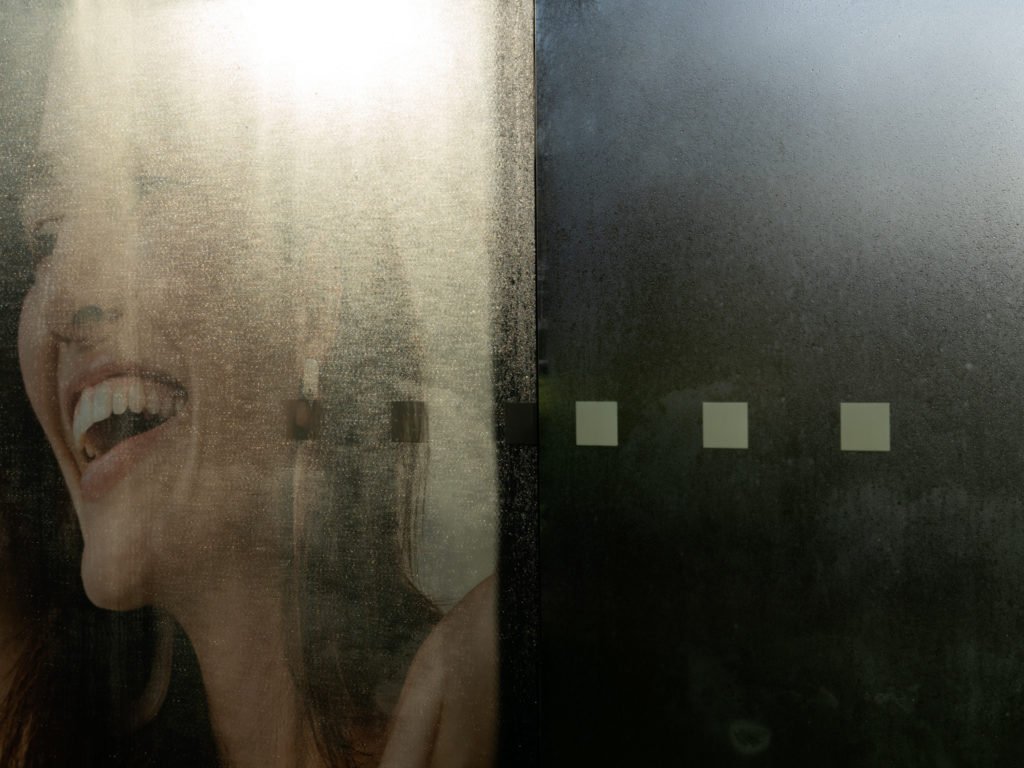

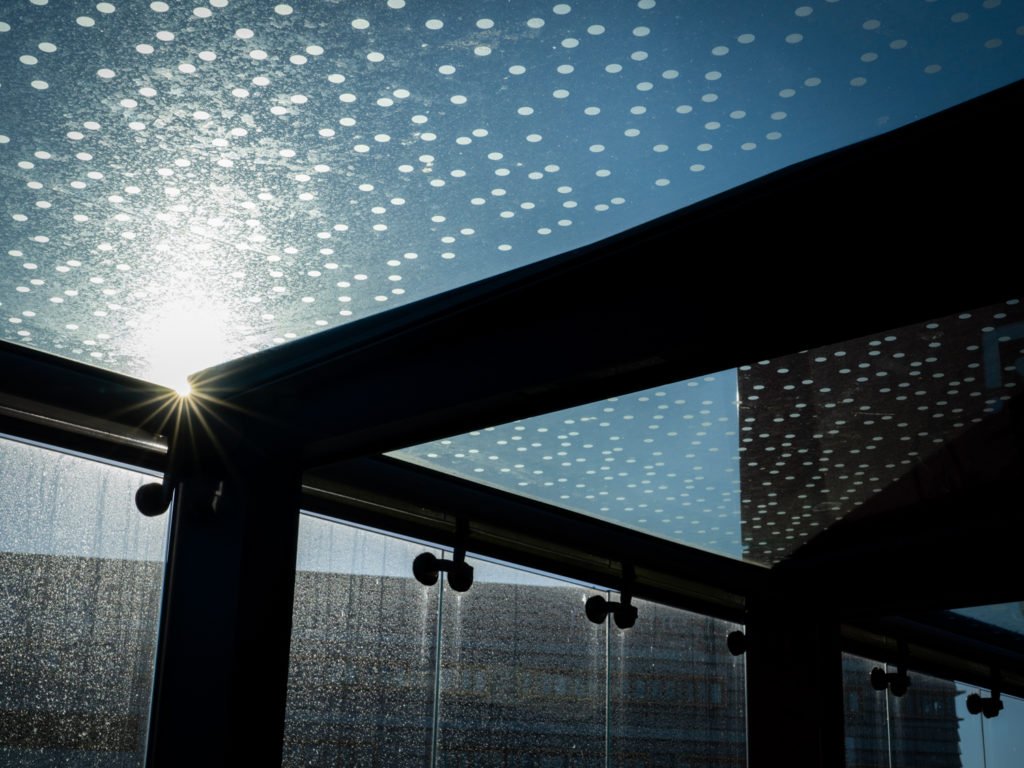

Chapter 2 — Suspended Time

In confinement, yesterday and tomorrow have been replaced by an endless today. Time is standing still.

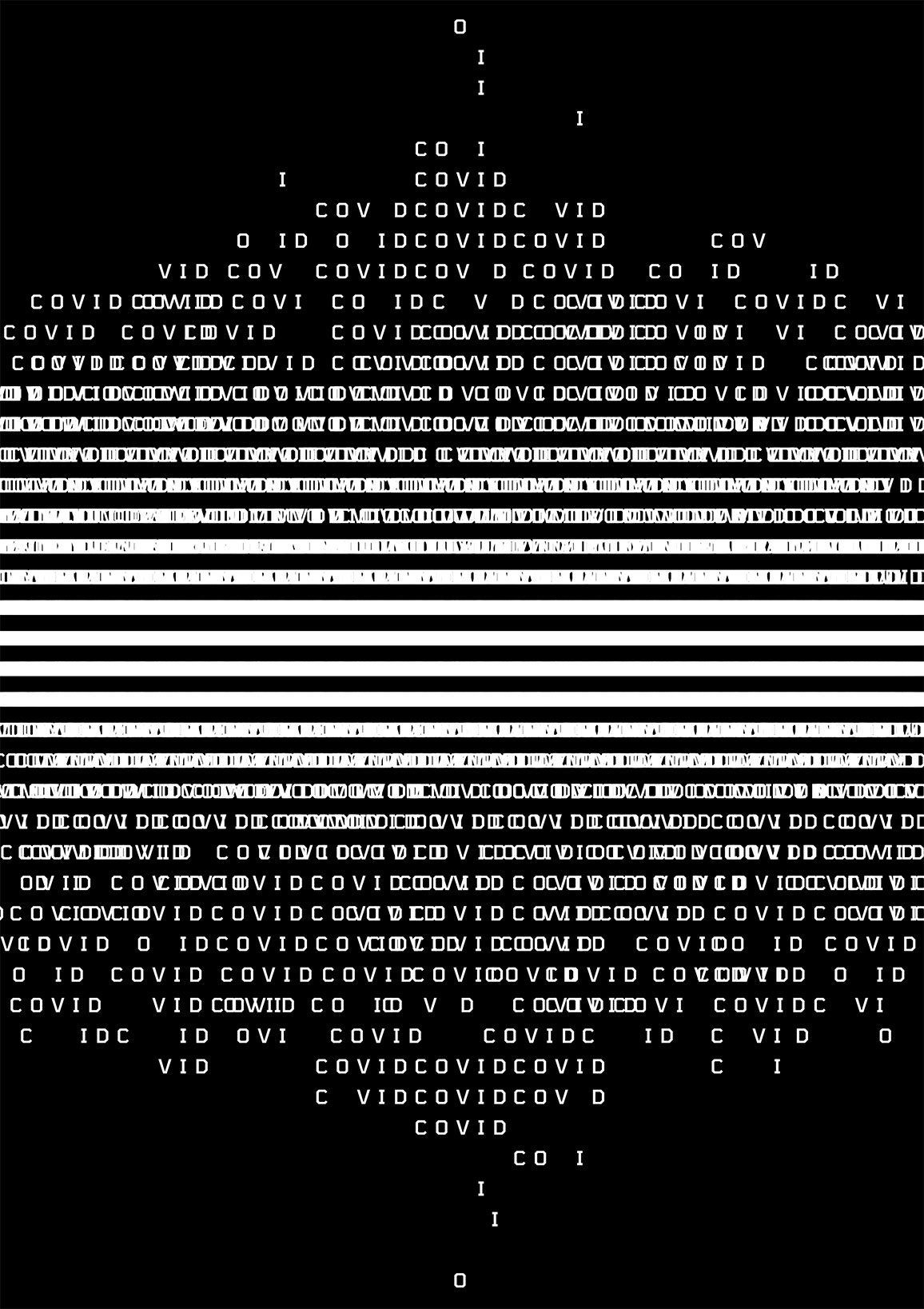

“Pandemic” graphic creation by Chiqui Garcia

BY CAROLINE LAMARCHE

Writer

What we see here makes us think of our daily lives in a strange way.

And yet these photographers have worked up until now in more turbulent parts of the world. Far from our ordinary lives. Close (or so we thought) to the “real” issues, the “real” problems.

Here, what we discover to our surprise is mostly stories that take the form of private or family diaries, of restricted walks.

But if we really think about it, was what they were doing before so remarkable? Wasn’t it, on the contrary, as normal and obvious as what human beings do day after day, and have always done: going to the frontline of their own lives, occupying the place for which they are destined, by circumstance or by vocation?

Coping.

(translated by Howard Curtis)

Read the full text here

Keep Hiding

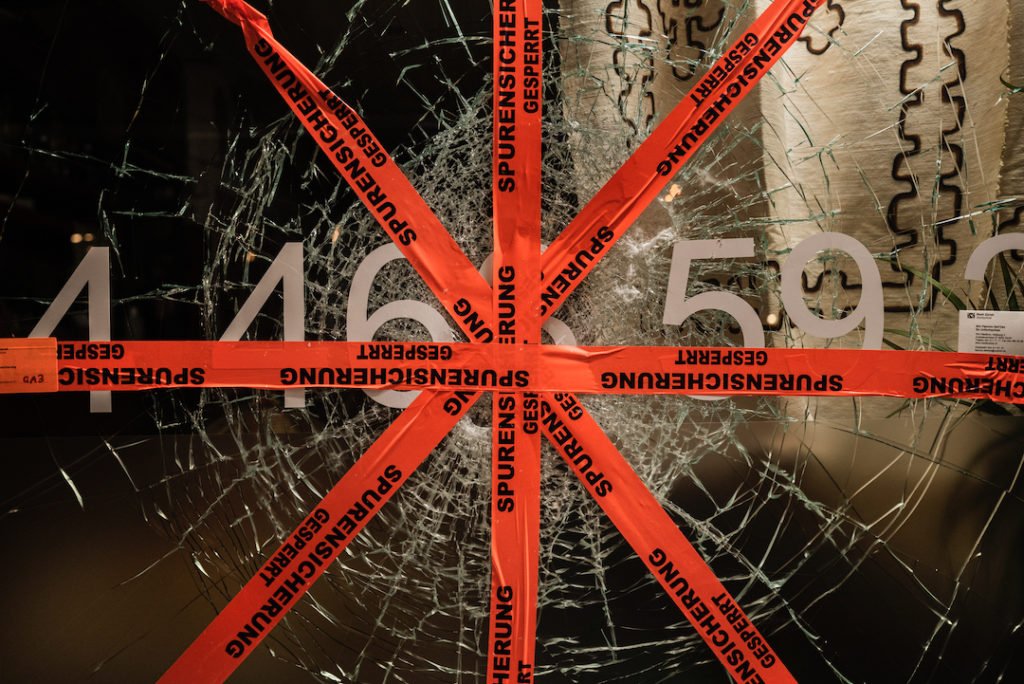

BY DOMINIC NAHR

I am very isolated here in my new home in Zürich. Even before the lockdown I would only walk from my apartment to my atelier and back, which is about four kilometers in total. I would avoid public transportation, public places and contact with other people would be at a minimum.

“I came to Switzerland to try and control my anxieties built up over 10 years of covering conflict”

I came to Switzerland to try and control my anxieties built up over 10 years of covering conflict. Although the current situation doesn’t change my daily life drastically, it gives me an excuse to keep on hiding.

Stay Home

BY ALESSANDRO PENSO

Through the use of smartphone video calls, I was able to interview and photograph people in different situations, in different parts of the world, to evaluate the effects of quarantine on people’s lives.

From those who have lost their jobs, to those who cannot see their children in prison, to those who do not have a home.

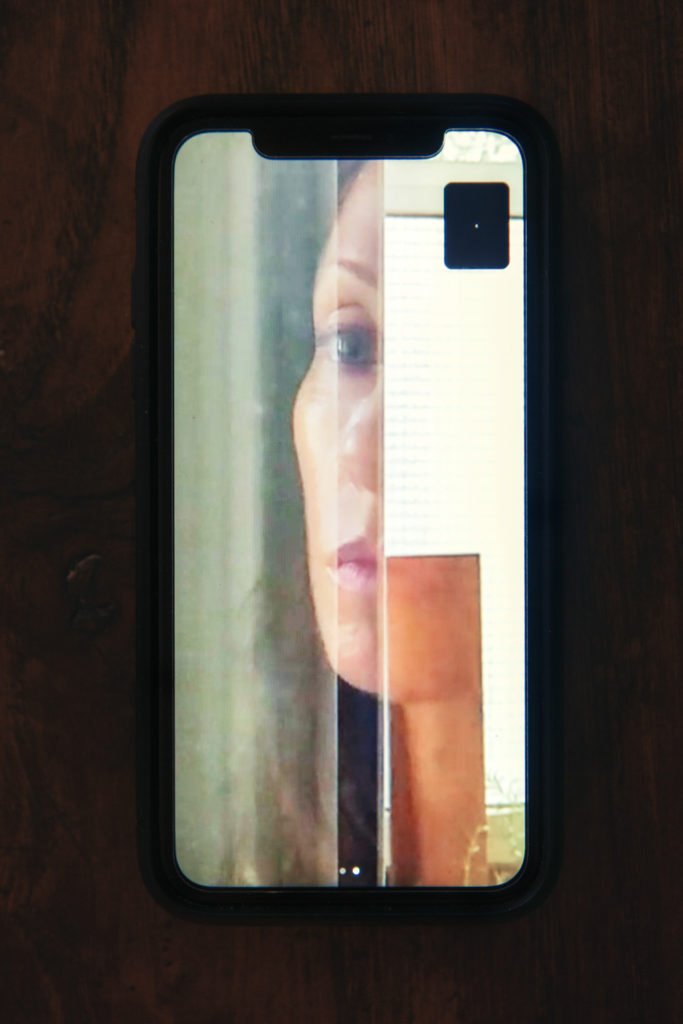

Above, Loretta Rossi Stuart, 52, mother of Giacomo, a detainee in Rebibbia prison, Rome, Italy.

“Prisoners are always last, and now they are more than ever.”

Giacomo dreamed of being a champion boxer, but drugs got in the way and he was arrested. A psychiatric report declared him “unsuitable for the prison system”. He should be in a treatment facility, but there are no places available, and so instead he has remained in an overcrowded jail.

With the coronavirus pandemic, his mother Loretta has been fighting to have him released so he can get the treatment he needs. But now, contact between her and Giacomo has become more difficult. Fears of the pandemic spreading within the prison system are high. Prisoners and guards have been tested positive, and there have been protests and riots in facilities over the authorities’ handling of the virus crisis.

“The state says to stay a metre apart. But there are six of them in 10 square metres in the prison.”

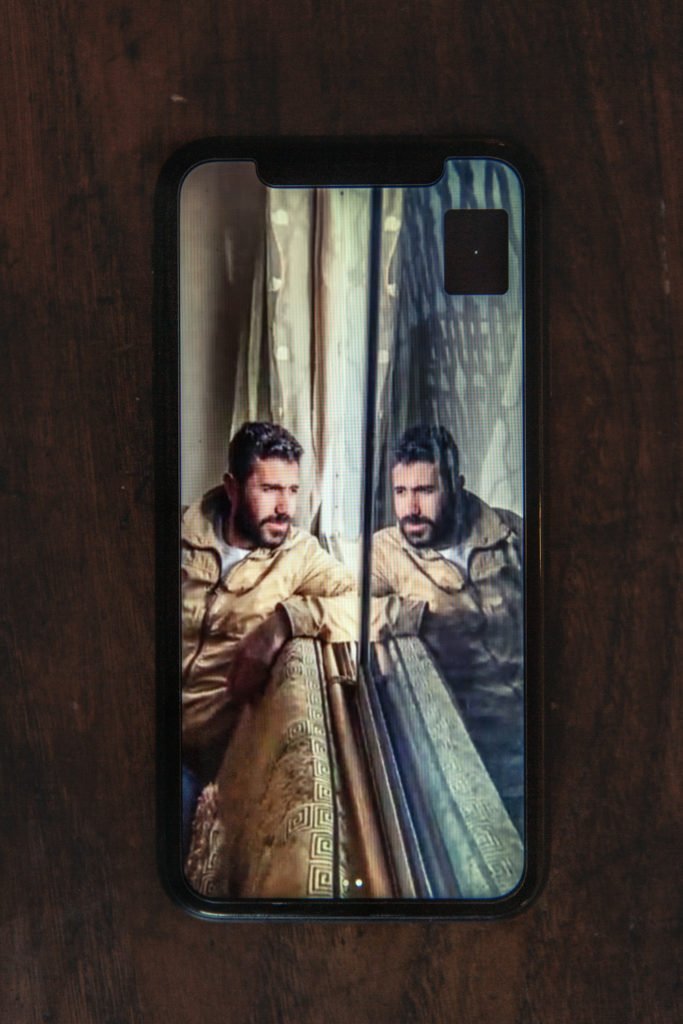

Above, Wahid, 24, asylum seeker from Afghanistan in the Moria refugee camp, Lesbos, Greece.

“If the virus reaches here, many people will die. There are a lot of elderly people. Many are sick, or have diabetes or heart problems that they aren’t getting medical attention for.”

Wahid arrived on the Greek island of Lesbos nine months ago. He is at the Moria refugee camp, waiting to finish the interview process to be able to apply for asylum. The refugees have been told to be careful and keep a distance of two metres, to always wash their hands and pay attention to cleanliness. In a camp with a capacity of several thousand that hosts 20,000 people, that’s all but impossible.

“I don’t have a choice, going back would mean death. Europeans are lucky to be born here. We are just unlucky, but this doesn’t mean we deserve to die.”

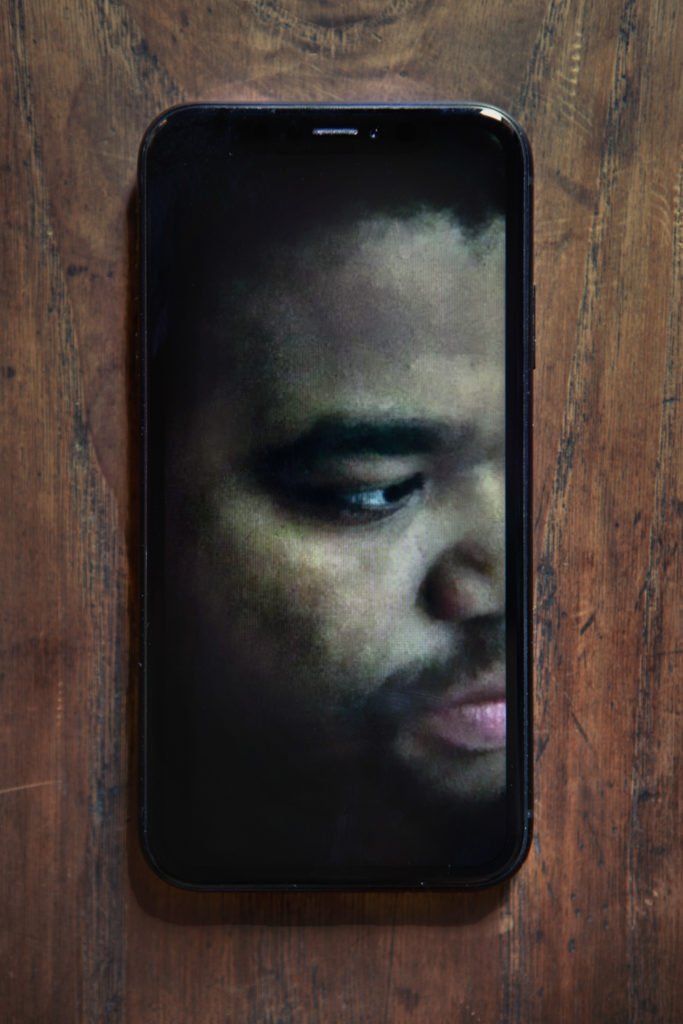

Above, Maria Consuelo, 34, sex worker, Bogota, Colombia.

Maria Consuleo lives in Bogota’s Santa Fe neighbourhood, where prostitution is tolerated and where around 3,000 women earn a living as sex workers. Maria doesn’t have a mask or gloves. She knows that in this neighbourhood, where people are poor and everyone lives on top of each other, an outbreak could be disastrous.

“There are eight people in my family – my mother, my disabled brother, my younger siblings and my children. They all depend on me and now I’m not working because of the coronavirus. There are many women like me here, supporting the whole family.”

Silos

BY KITRA CAHANA

In Tucson, Arizona a State of Emergency was declared on March 17th, 2020. In the days since many locals gravitated towards the natural environment, going on hikes around the city and soaking up the last of the open outdoors before going into isolation.

I spent a day driving around Tucson looking for isolated scenes that show the surreal nature of what is going on — from afar.

“Many locals gravitated towards the natural environment, soaking up the last of the open outdoors before going into isolation”

More chapters from the Coping collective project

In the face of a global, unprecedented crisis, coping may mean to find shelter within the inner core of what constitutes a safe environment. Holding onto the thread of transmission, finding comfort in familiar places, with loved ones.

Every crisis involves an aftermath. How to apprehend it, how to imagine rebuilding our future lives in the midst of the turmoil?

More Series by Maps Members

Best Images of 2017

Maps Members

A selection from the best images of 2017 by MAPS photographers

MoreThis was 2019

Maps Members

2019 has been a time of exploration and discoveries. Of reflection and coming together. Of defining and redefining what MAPS…

MoreYouth for Climate: New York, Brussels and Lausanne

Maps Members

All over the world, young people take to the streets to demand action on climate change. John Vink has been…

More